Background #

In my first post, I went through at a high level the GitHub attack surface and different areas for Red Teamers to research and look to exploit. In this post, I review the GitHub CLI (gh), looking at the functionality it provides and potential ways an adversary may look to abuse it.

But why would you care about the GitHub CLI? Recently authenticating into GitHub is becoming more challenging, specifically if you want to do development. It fundamentally comes down to some form of access token and there are a limited set of tools that can do that. For the CLI, GitHub directs you down the route of GitHub CLI as such we’ll likely see more developers turn to the tool to authenticate with their repositories and associated organisations.

Examining the GitHub CLI #

Examining the CLI, the following options are presented back:

|

|

To manage anything remotely will require authentication (auth). To confirm we can issue a command to manage an extension or attempt to make an authenticated call to the GitHub API.

|

|

|

|

Let’s determine what we can do unauthenticated. Looking at the config command we can see a few interesting settings, specifically the git protocol and the web browser.

|

|

The two options available are https and ssh.

|

|

If we use https we’ll be redirected to the user’s browser to authenticate with GitHub but if we can change the config to ssh and the user configured an ssh key with GitHub we can possibly avoid the use of a password and two factor authentication. Let’s try changing the configuration.

|

|

Great, so we can achieve the first stage. Let’s try and see if we can use an ssh key for authentication.

|

|

|

|

Now we’ve confirmed we have access to the key, let’s see if we can authenticate with GitHub with it.

|

|

Unfortunately not. We are asked to authenticate and we can point to our ssh key but we are immediately asked for an existing token or to login with a web browser.

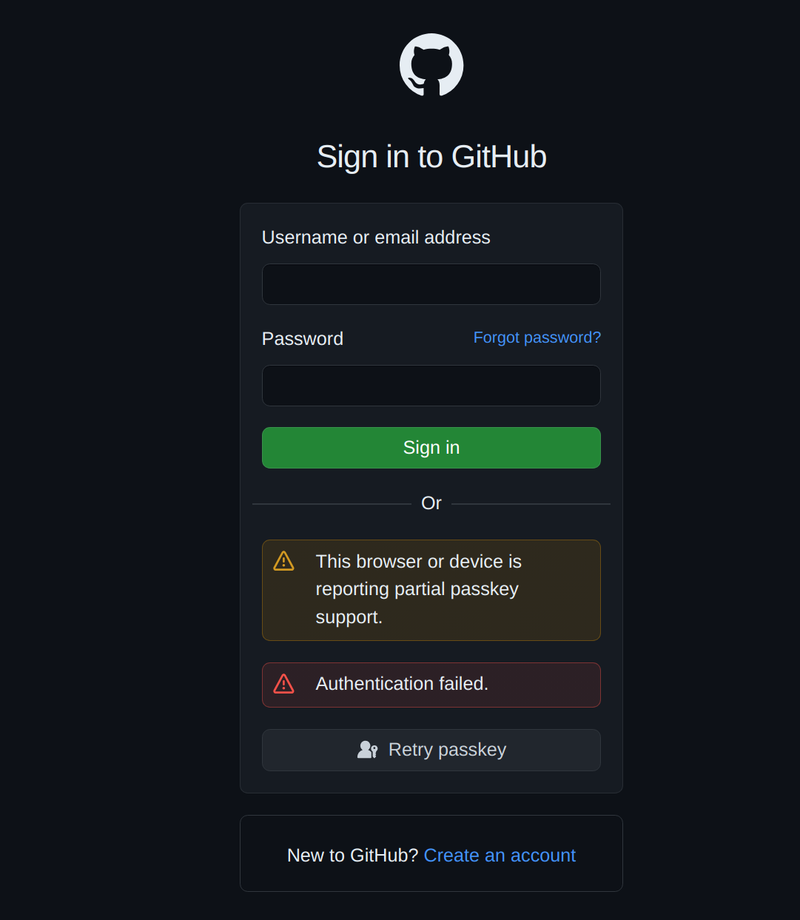

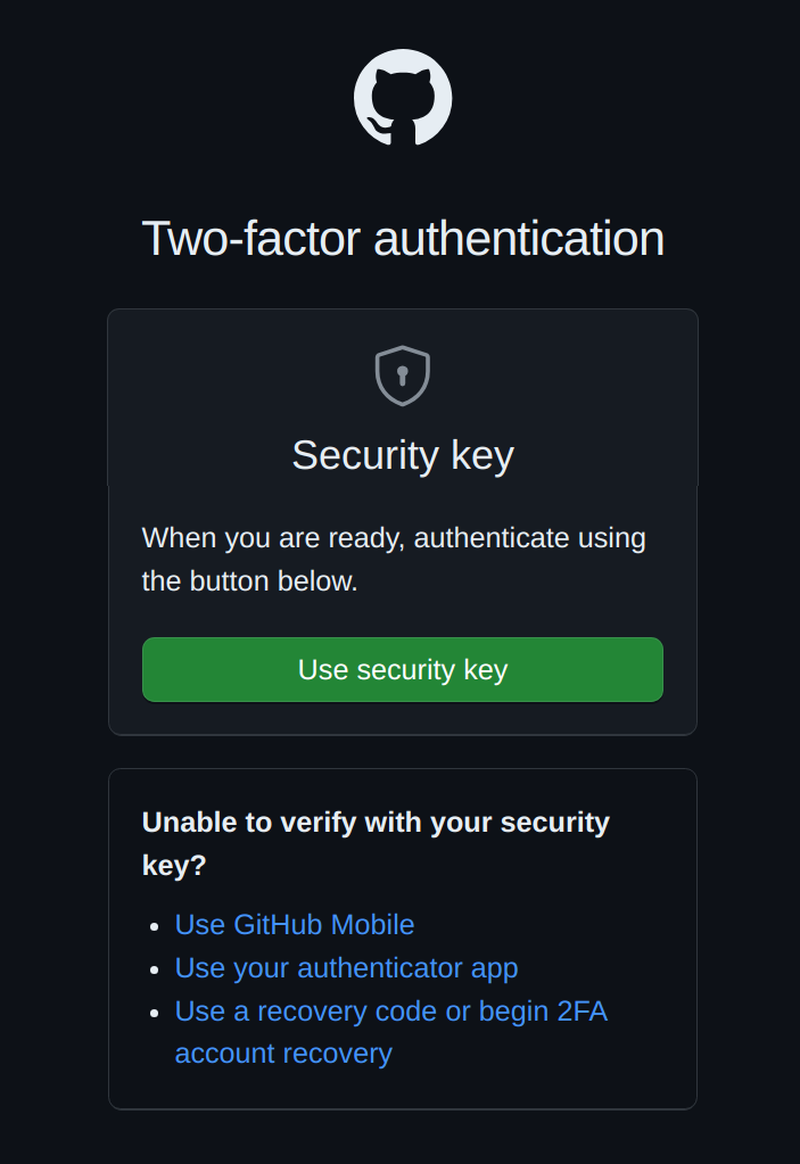

If we continue with the web browser we are greeted with the normal browser authentication flow.

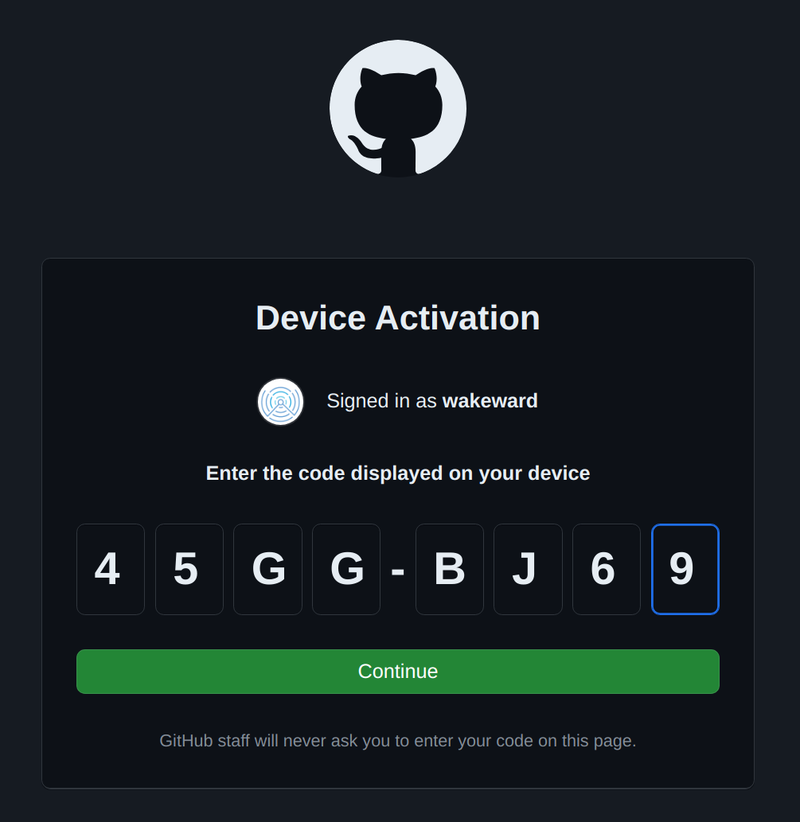

Once we are finished we need to pass the one-time code provided.

Returning to the CLI, we are now authenticated.

|

|

GitHub CLI Tokens #

So what have we learned from this test?

GitHub is dependent on the browser for authentication. If we compromise a browser we can look to intercept the authentication flow or at least determine when an user has authenticated to GitHub. If we have an implant on the local device, we may not want to proxy connections and wait for the user to authenticate using the GitHub CLI. Interestingly we can change the configuration of the browser if we wanted to.

Using the ssh protocol for git does not further our access, only defaulting how we interact with git. If we want to leverage a user’s GitHub account, we need a token. It is a matter of whether the user has an active token and how long does the token last.

Before we delve into what we can do with this token, how do we obtain a token from an authenticated user and how long it lasts?

The GitHub CLI provides an option to retrieve the token via gh auth token.

|

|

To determine how long this token lasts, we can refer to the documentation. From this we know that a GitHub CLI token will last for one year:

GitHub will automatically revoke an OAuth token or personal access token when the token hasn’t been used in one year.

And it will be revoked if pushed to a public repository or gist

If a valid OAuth token, GitHub App token, or personal access token is pushed to a public repository or public gist, the token will be automatically revoked.

We’ve got a token but where is it actually stored in our system?

Fortunately the tool is open source and can be found here: https://github.com/cli/cli. Let’s go through the code.

- The tool is written in go so the

authcmd option is probably a package and we can see this in login.go. - When a new login cmd is run, it sets a number of options including config which is imported as a package

github.com/cli/cli/v2/internal/config. - After executing some checks it eventually invokes loginRun.

- The authentication configuration is set as

authCfgcalling the config package. - We eventually end up invoking the

Loginfunction within the config package which uses a keyring package to set the secure storage for the token.

For Linux we can validate this by using the keyring command.

|

|

To execute keyring, we need an operation, which in this instance will be get, a service and a username. The username should be the GitHub username (wakeward) but we need to know the format for the service.

We know from walking through the code, that the service set for the keyring is keyringServiceName(hostname) which is returned as "gh:" + hostname. The hostname if not set will prompt the user for two options:

|

|

So based on this our keyring query should look like the following:

|

|

Bingo!

One interesting finding is there is a parameter for the GitHub CLI which is a boolean for using InsecureStorage that if set will save the credentials in plain text. Although this is interesting, we are considering the case that we’ve compromised a local user’s environment so as we’ve discussed, if they are a developer with the GitHub CLI and have previously authenticated, can just invoke the gh auth token to grab the token value.

Token Reuse #

Now we have a GitHub token, can we use it on another system? Let’s give it a try.

From the GitHub CLI we can pass in a token via:

|

|

So if we copy our Token over to another system and login using it, we should be able to retrieve private repositories.

|

|

Nice! But why do all this work?

When you are building out a threat model it is so important to check ideas you may have or any assumptions you make about a system. In this instance, we have tried to access GitHub via the CLI without a token and found it is not possible. We have also determined the expiry of the token (although we haven’t checked whether it actually is valid for a year!), found out where it is stored and that it is transferable. Lastly, we’ve dug into how the GitHub CLI works, following the code flows and discovered that we can pass a flag to output the token as plain text.

GitHub CLI Extensions #

We have exhausted our review of the auth command, so are there any others that look interesting? The remaining CORE COMMANDS seem to be regular methods of interacting with GitHub and GitHub Action commands seem to be focussed on auditing workflows which is likely limited to information disclosure. This leaves the ADDITIONAL COMMANDS section which a few catch the eye. The first is extensions which allow the developer to manage internal and external extensions to the GH CLI. The next commands are secret, ssh-key and variable which all allow the management of sensitive configuration settings such as GitHub secrets, SSH keys and GitHub Actions variables respectively.

Let’s focus on extensions as they are a way for an adversary to load malicious code into a developers environment.

Creating an Extension #

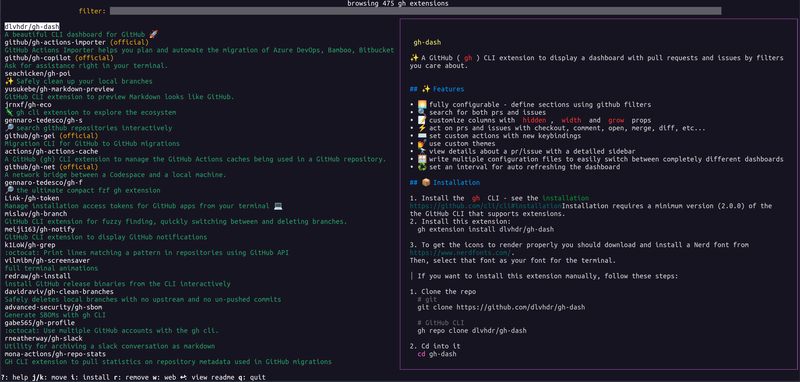

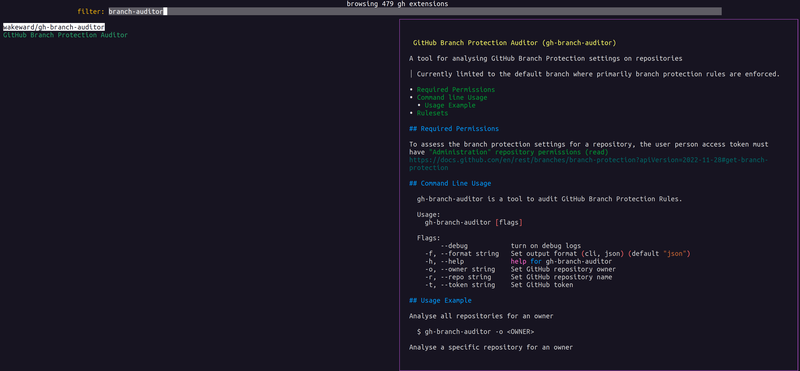

GitHub CLI extensions can be viewed by the following command:

|

|

If the extension is published by GitHub it is given the (official) label whilst community provided extensions, even those provided by organisations, do not. An extension can take many forms as indicated by the Official Documentation.

There are a couple of options here:

- Interpreted extension - used to make an extension with python, ruby, javascript etc.

- Go precompiled extension - used to make a go compiled extension (i know obvious right!)

- Non-Go precompiled extension - used for languages with java but requires a build script to defined so it can support cross platform integration

- Interpreted extension manually - define a script to execute extension functionality

Let’s create a simple extension and see what is required to get it available in the GitHub CLI extensions list. I’ve chosen golang for this extension as from a security perspective creating a random binary for execution on another user’s environment is one of the objectives for an adversary and I’m interested in the level of scrutiny they are given by the GitHub team.

The extension I’m going to create is provide a quick view of the current branch protection settings for a repository and provide an overview of the risks of not having those configured.

Based on the documentation, extensions must fulfil this criteria:

- The name of the extension must begin with

ghand be followed by the extension name - The compiled binary must be located in the top folder with the name of extension

|

|

Running the command initialises a git repository with template files.

|

|

The main.go is configured with a simple hello world example to be able to compile the binary.

|

|

I won’t go through the entire development process for the extension but If you want to review the code, it is located here: https://github.com/wakeward/gh-branch-auditor/.

Regarding branch protection rules and the risks I’ve provided as part of the tool output, I may return on that topic as part of this Red Teaming GitHub series.

Uploading to the GitHub CLI Marketplace #

With a working extension created, how do I publish it to the GitHub CLI marketplace? Once a release is created, the repository must have the topic of gh-extension and this will make the extension searchable via the web interface or gh extension browse.

It is unclear what security auditing is performed on GitHub CLI extensions but there is a warning about using Extensions outside of GitHub and GitHub CLI are not certified by GitHub.

Extensions outside of GitHub and GitHub CLI are not certified by GitHub and are governed by separate terms of service, privacy policy, and support documentation. To mitigate this risk when using third-party extensions, audit the source code of the extension before installing or updating the extension. Based on this, I believe there is very little assessment happening to these extensions so tread carefully.

You may think that a source code review will allow a consumer to validate what the extension is doing. Be aware, there is nothing stopping an adversary presenting benign code within the repository and push a different malicious version as the release. The documentation provides an example to push a release manually.

Threats #

There are few threats to consider for the GitHub CLI. Firstly, it is highly likely that a developer is authenticated with the application. So if you manage to obtain local access to the developers device, it is trivial to dump their GitHub Token which is transferable and unless revoked, will last for a year.

GitHub CLI extensions can be used to run arbitrary code on the developers environment. The primary issue is tricking the developer into downloading and running the extension. This goes back to existing techniques such as social engineering or typo squatting a popular extension in the hope a developer will accidentally use it. It is possible to sideload an extension via the GitHub CLI so a developer could open a malicious file from a phishing email which would install and execute the extension. This could be an interesting place to hide a malicious executable but you cannot avoid any security tool looking at the process tree or seeing an outbound connection.

A more sophisticated extension could be made which steals the GitHub Token, encrypts it and sends it to GitHub. The nice part of this attack is that we already know that GitHub will be allow listed and it’s rare for outbound gateways to restrict based on specific repositories. I could create a code sample to demonstrate this but as the GitHub CLI provides the majority of the functionality to do this, it seems superfluous.

I hope you have found this article insightful in how an adversary can leverage the GitHub CLI to obtain code execution or steal long lived credentials to potential sensitive source code repositories. If you are a Red Teamer and find it useful or it inspires a campaign, feel free to reach out and let me know.

Next up in Part 3, I’ll be reviewing VSCode Extensions and how they can be abused by adversaries.